Dr. Thomas Sopanen, a retired Finnish botanist, recently made a name in Minneapolis when his fabulous collection, The Living Tradition of Ryijy – Finnish Rugs and their Makers, was displayed at the American Swedish Institute in 2014. To FinnFest 2017 he brought a smaller, but equally important collection of weavings, this time the exquisite damask weavings of noted Mid-Century artist and designer Dora Jung.

Organizer Anita Jain offered me a special tour and presentation to share with my friends, and on Saturday, September 23, you couldn’t have found 18 more avidly-interested weavers anywhere than in Studio Ella in the Northrup King Building.

Dora Jung, 1906-1980, was one of the most important textile artists in Finland. Her work is represented in museums throughout Europe and in the Smithsonian. Locally, MIA owns two pieces.

Dr. Sopanen’s interest in Jung was sparked by seeing “Katarina Jagellonica,” at age 16 in on a visit to a castle with a class trip to Turku. “I even remember the color of that red book,” he reminisced.

Her father and uncle were both noted architects. She was not robust as a young person, and her father bought her a loom, thinking it would help. It did! She finished studies at the Central School of Applied Arts in 1932, and began her own weaving studio that year, first in her parents’ home.

She chose damask as her medium, a complicated and challenging weave structure. She traveled to several countries to learn more about the technique. Through her career she developed her signature technique, moving damask away from traditional symmetrical patterns on fabric yardage or table linens, to using multiple colors in asymmetrical images for art pieces.

From the beginning, she employed other weavers to execute her designs. She was often under or beside the loom, but rarely weaving. She felt if she was the one doing the weaving, she would be distracted by experimentation.

At the beginning she concentrated on table linens and upholstery textiles.

During WWII, when linen yarns were needed for the army, she began to weave with paper yarn–the cheapest of materials, the most complicated weaving technique. She rarely wove images of contemporary events, but during the war she wove “The Transport of Children,” describing the situation when Finnish children were sent to Swedish families during WWII. (I don’t have an image of that piece.) Another later work (1970) that is notable for its comment on current issues was a piece depicting children affected by famine in Biafra. This piece is not from Dr. Sopanen’s collection; the image is taken from this Finnish blog post.

She wanted to get rid of the restrictions of weaving damask, and “Peacock,” woven for an exhibit in Sweden in 1946, illustrated her experimentation. This was the first time she made an art textile, to be hung on the wall; damask came up from the table. Dr. Sopanen was able to buy a version of “Peacock.” Jung used one large central figure, rather than the typical allover pattern on damask pieces. She used color in small areas, another innovation. And isn’t it interesting and brave that she included her obvious testing areas in this final piece?

During her career Jung wove around 600 liturgical textiles, which don’t often come up for sale to a collector like Dr. Soppanen. He felt lucky to purchase this weaving done as a sample for an altar cloth commission.

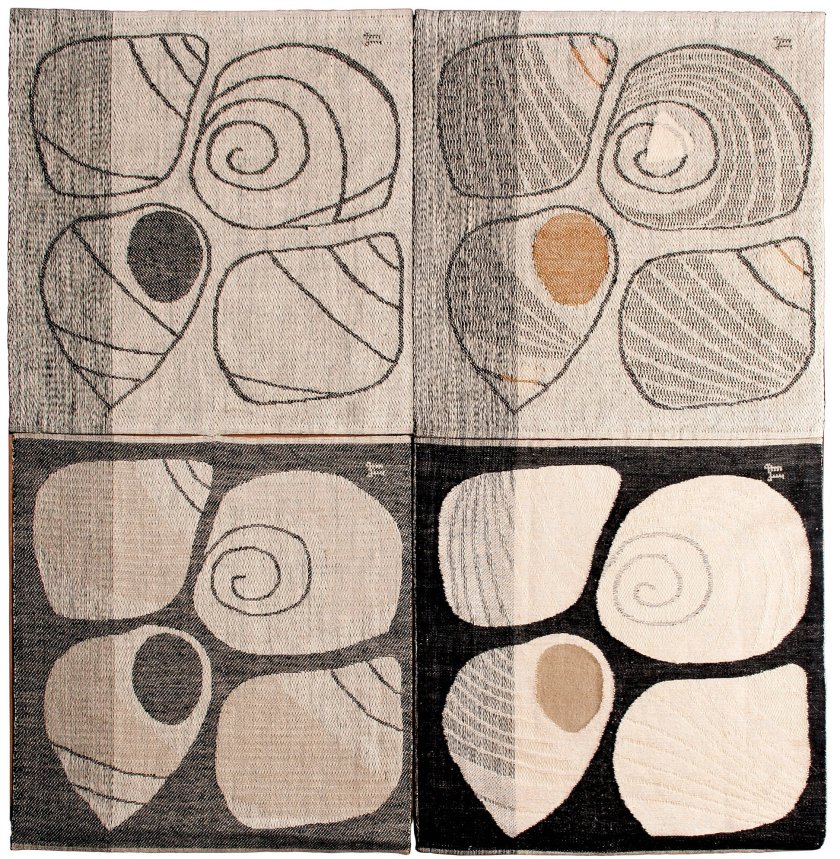

The series, “Shells I-IV,” 1957, was a woven response to the question, “Why are pieces of the same size different prices?” The first one was straight damask weaving. The second had more detail and took two days to weave. The third one took four days. In the final piece, the whole background was done with very fine yarn, and it took eight days to weave.

When discussing her work, she was modest about her accomplishments, but constantly praised the weavers who executed her ideas. And even though she didn’t weave so much personally, she preferred to be known as a weaver, rather than as a textile artist. She told buyers of her smaller pieces that they could be on the table or on the wall, and when exhibiting them, showed them both ways. (Below–two of Dr. Sopanen’s fish pieces.)

Part of the joy of seeing the weavings of Dora Jung and learning about her career was listening to Thomas Sopanen talk about his life-long quest to collect her work. His admiration for the artist was infectious. For example, her bird panels were among her most notable pieces. Her first set of three bird panels won the Grand Prix at the Milan Triennial in 1950. She wove several versions, and Dr. Sopanen hoped to acquire one, after seeing them as a young man. Though they seldom came up for auction, 45 years after his started his quest, his luck finally turned. He told us, “If you have hopes, and you wait, they may come true.” One dream has passed, however– to visit her studio. As a young man studying in Helsinki he was too shy to visit her studio; he felt she was too renowned.

In all she wove more than 100 pieces with doves, an amazing assortment. While many have similar outlines, there are always subtle differences in color or details. “That’s one thing I admire about her work — she doesn’t repeat herself,” Dr. Sopanen said.

After making a large art piece, Dora Jung would often weave other pieces using elements of the design. Dr. Sopanen owns two pieces with vases.

They are elements from a larger piece (which he does not own), “Quattro.”

Dr. Sopanen admired her embodiment of Finnish ‘sisu,’ or perseverance, and her devotion to her art. There were lean years when the studio took on commissions that strayed from her art practice; between 1955 and 1957 her studio produced 5400 meters of fabric for radios.

Dora Jung designed commercially-produced textiles as well as the work done in her studio. With the development and popularity of contemporary ceramic tableware, there was a need for linens that would complement them. She designed her first tablecloth, Grafica, for the Tampella Linen factory in 1956. In 1957, she won her third Grand Prix in Milan for her tablecloth, “Play of Lines.” This tablecloth was often given as a gift of State to other countries by the Finnish government.

When FinnAir began its service to New York, they highlighted the work of Finnish designers. First class travelers enjoyed dinnerware by Tapio Wirkkala and specially designed linens by Dora Jung.

This opportunity to hear a lecture about Dora jung’s life and see her work, along with many other appreciative weavers, was a wonderful gift. I play a game with myself when I see weaving I love. If I was locked in a room and had to reproduce the work, or else go to jail, could I do it? In the case of Dora Jung and her complex, experimental damask work, I would totally be in jail. Maybe with the help of my friends Kelly Marshall and Phyllis Waggoner I could be taught. I leave you with a final, favorite piece from Dr. Sopanen’s collection.

This opportunity to hear a lecture about Dora jung’s life and see her work, along with many other appreciative weavers, was a wonderful gift. I play a game with myself when I see weaving I love. If I was locked in a room and had to reproduce the work, or else go to jail, could I do it? In the case of Dora Jung and her complex, experimental damask work, I would totally be in jail. Maybe with the help of my friends Kelly Marshall and Phyllis Waggoner I could be taught. I leave you with a final, favorite piece from Dr. Sopanen’s collection.